Case study: PIDs in Publishing Workflows

Introduction

At a recent focus group, convened by the THOR project team and made up of publishing experts from a range of organisations, covering articles, books and data, and representing a variety of organisations (commercial, not-for-profit, open access, subscription, large and small), the opening discussion was centred on a seemingly simple question:

How would persistent identifiers be used in an ideal world?

The consensus was that this ‘ideal world’ would be one in which persistent identifiers (PIDs) are used effectively, optimally and ubiquitously in publishing workflows.

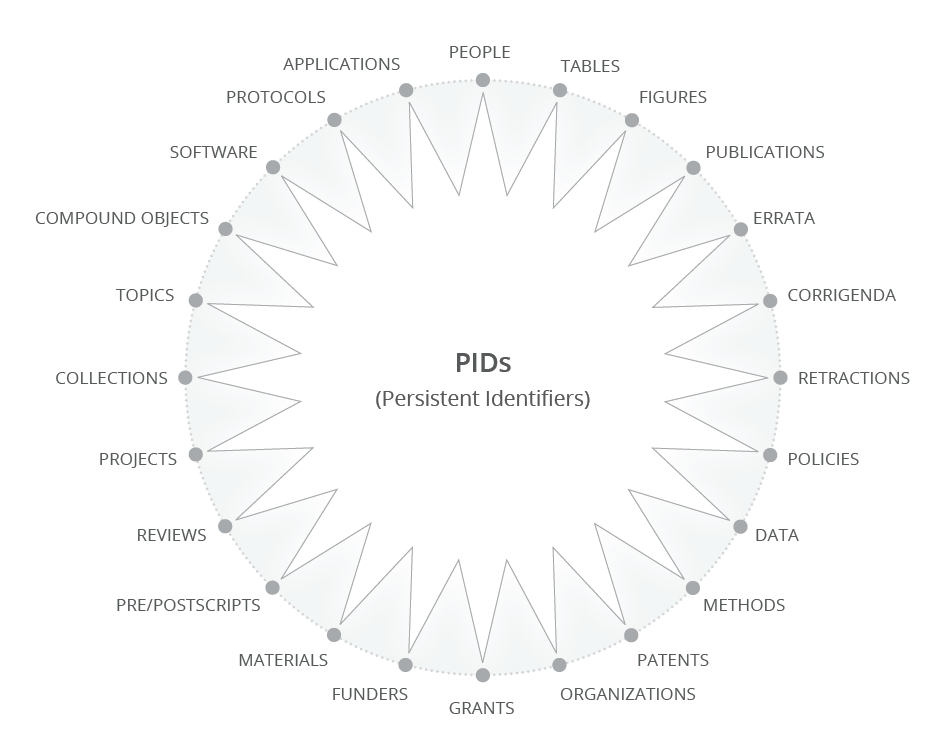

Over the course of a short round-table discussion, the participants came up with a list of things that could, and should, have PIDs right now. All of these could be uniquely identified, and could be related to any of the others on the list. We represented this ideal world with this graphic:

The features of this ideal world included:

- Publishing platforms and vendor systems would support ORCID and PIDs out of the box.

- There would be authentication for all contributors.

- Relationships and roles to be machine readable (for example - citations or types of citations).

- All the PIDs we use would be FAIR.

- There would be consistent data/software/article versioning that actually works.

- We would be able to represent collection of things via a network of connected PIDs.

- Publishers would achieve a consensus on the industry’s ‘wishlist’ for PIDs and standards.

The world was characterised as one in which reliable, dependable PID infrastructures (with zero downtime) were constantly delivering tangible benefits, such as time and effort savings, to researchers and others. In this world we would never have to make the business case or argue for the value proposition of PIDs. We’d be too busy reaping the benefits of using them.

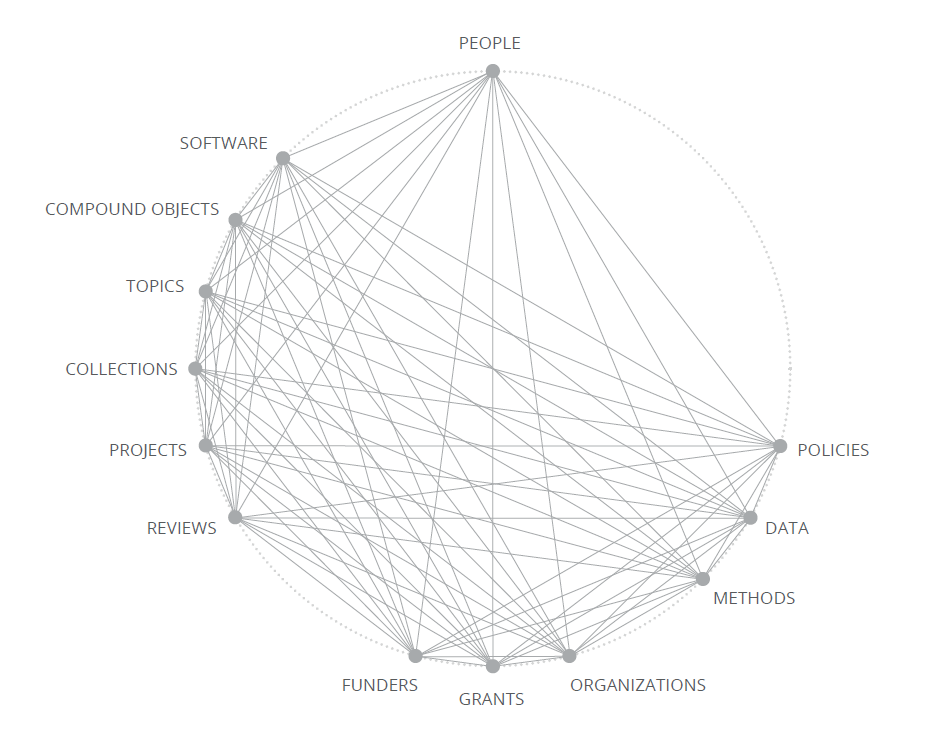

Ultimately, what we would like to see is a world in which a network of PIDs and the relationships between them can be used to capture the whole web of connections between things. The power, and value, of the network is made obvious when one considers it as a graph. The diagram below shows an example of what such a graph could look like, taking an example of just those nodes which are relevant to a particular dataset:

When all these connections are possible, a rich and precise understanding of the origin, relationships and potential of the dataset is easily achieved.

Over the course of the focus group, participants discussed specific publishing processes, and discuss their current pain-points, successes and ideas for how PIDs could be used to improve the quality and volume of information available for use, re-use and analysis. This discussion paper summarises some of the thought provoking, and sometimes provocative, ideas that emerged during those discussions.

Manuscript submission

How can we improve the use of PIDs within the submission workflow? A number of manuscript submission systems enable publishers to collect ORCID iDs. Some of the biggest challenges mentioned in the discussion are rather social than technical: Raising awareness and promoting the benefits to authors so they can make full use of their ORCID iDs, because when the full benefits are unclear, people end up with empty or incomplete records. This is not just a task for publishers: institutes could also make an effort by explaining the benefits of Single Sign-On and putting up posters explaining the benefits of ORCID. That said, the technical challenges are real and concern the exchange and re-use of information between systems.

Examples cited in the discussion included: While iDs are often collected during manuscript submission, they need to be exported and used in other systems before they can be included in the final publication. It should be made easier for authors to find additional information in ORCID records when they are submitting their manuscript. Adding to the record ends up being an additional hurdle because it is an interruption to the submission process. Navigation to help pages on the ORCID website should be improved and publishers could also improve communications by stating the reasons they are collecting ORCID iDs in their submission instructions and emails to authors.

Making the ORCID record multifunctional in the publishing workflow could be an additional incentive for authors; they will not only use their ID for submissions but also for post-publication comments. Communication on the benefits of pre-population could also be improved: Authors should be made aware that if their contact info in ORCID is set to private this kind of autocompletion functionality does not work.

Publishers could work together on improving the workflows for the collection of co-authors’ iDs. This is currently possible in Editorial Manager but this process could be optimised. Autocompletion of co-author lists would be a great benefit. Project identifiers, with people’s ORCID iDs included would be an advantage. Another possibility to collect iDs would be SMID. Ideally iDs will be collected via SMID and then pushed into the publishing system automatically. However, SMID as it currently stands would be yet another system or interface to add to the submission process, so it would be best to include similar functionality in core publisher systems.

Funding information

Is it possible to make funding information more accessible through PIDs? Currently, adding a funding identifier during the submission process (e.g. in Editorial Manager) is often optional. And most funding information is free text that often gets mistyped. Some submission systems autocomplete the funder name and that information is exported to the article’s metadata. Some submission systems ask authors to tag which authors used which funding. Other publishers are text mining to extract the funding information - because funders are asking for it. But this just connects the funder to the paper – not to the authors. Clearly, funding attribution could be improved by using PIDs.

ORCID iDs could be used to connect funding information to the authors and ideally this would be done during the submission process. However, the variety of ID numbers for grants make this problematic – they cannot be validated. Funders should provide a list that authors can pick from. Therefore, using a grant ID database to solve these issues would be highly recommended.

Another clear benefit of using PIDs for funding attribution is that authors will be able to comply with Open Access regulations more easily. This can for example be done through Rightslink (CCC) as this system handles the data for invoicing Article Processing Charges (APCs). It would be valuable to link to the funder to ensure subsidies for APCs are used (when they are available) and the required licence could be attached. This also means the invoice can be sent to institutions rather than individuals. Funder notifications upon publication would be a huge benefit. In some cases, these need to be linked to organisation IDs, not fundref IDs. For example when national institutions pay APCs.

Preprint integration

Using PIDs for preprint integration in the publishing process is challenging due to a number of reasons. Some systems (e.g. arXiv and bioRxiv) do have preprints with IDs but these are not connected. In addition, the transfer between different systems is very complicated or impossible (e.g. from Overleaf to Editorial Manager or even between different journals with the same publisher). Some publishers offer direct preprint submission, but ORCID iDs often do not flow along with the manuscript.

ORCID iDs can help to integrate preprints more readily into the publishing workflow. Transferring the ORCID iD and any associated data along with a submission would be a real plus. Various routes on how this could be done are discussed, e.g. ORCID initiated workflows or via CRIS systems at institutes. It would also be valuable to be able to assert related items in an ORCID record, e.g. group pre-prints with published articles.

Post publication information

Another point that is discussed is whether or not authors would prefer preprints to be added as a separate work type. These work types could be linked to the published paper (if one exists). If preprints were to be added as a work type, a clear definition of the term “preprints’ is needed.

Using PIDs for post publication information can be difficult. This is related to changes to the publication date and the differences between online publications and printed materials. However, using ORCID iDs for some parts of the post publication process would be valuable.

ORCID records could for example be used as a means for sharing updates, e.g. if a paper is retracted, the publisher can push information to the ORCID record directly instead of Crossref or DataCite. Currently, retracted publications are in Crossref but not linked to ORCID iDs. This is a good argument for publishers to push information directly to ORCID records. When the information is pushed directly to the ORCID record, it enables direct messaging to the author. This will take away confusion for the authors which is very valuable in the retraction process.

Another way of using ORCID to share post publication updates could be the implementation of Hypothes.is for comments. Having the ORCID iD to login to comment will provide links. This could perhaps be done by showing the Hypothes.is profile in the record and details of activities in the profile page. Describing “part of” relationships is currently possible within the ORCID record but we might need to add more complex relationship types.

Conclusions

The consensus in the room was that in general, we already have a great deal of what we need to achieve the ideal world vision. PIDs for people (such as ORCID iDs), for data, for funders, for publications are all commonplace. There are widely used platforms and services that can provide DOIs for figures and tables.

The group felt that we are ‘nearly there’ with many other things: organisations, grants, patents, historical data were all cited as examples.

However, while there are infrastructures in place, they are not consistently integrated. The ‘out of the box’ PID integrations are not universal, and are not reliable. This unpredictability is a huge problem, as it obscures the benefits of PIDs as well as slowing progress towards the ‘complete graph’.

Authors do not generally like to use machine-readable tools. A DOI is meaningless to the average researcher. Without ubiquitous integrations that can resolve and display the information a PID references on the fly, generating a human-readable view, adoption will be harmed by a perception of user unfriendliness. When the user experience of PIDs is consistent and accessible, we will be able to rely on the presence and use of PIDs much more.

The lack of awareness of linkages between PIDs further slows adoption. However it is further worsened by fragmentation. As an example, historical data is being made machine-readable, but in different ways by different groups. We need to find a means to stitch the past and present together within a common framework of PIDs and standards.

These problems are real, but the most significant gaps identified during the discussion were in the tools to make connections between PIDs. The means to capture and describe all the relationships between PIDs has not been found, and without it, we cannot compose compound objects. When we can, they will need their own PIDs.

The biggest challenge for existing systems is to generate the levels of adoption that will deliver something close to ubiquity. As we work towards that, however, we should not lose sight of the absolutely critical missing components needed to reveal the entire graph. While we strive to fill those empty spaces, we must continue to raise awareness of what is already possible. By increasing the adoption of PIDs, we increase the understanding of their value and ease of use. This momentum will help us to complete the PID graph.

Updated less than a minute ago